Reading Data

Overview

Teaching: min

Exercises: minQuestions

Objectives

Loading data into Python

In order to load our inflammation data, we need to access (import in Python terminology) a library called NumPy. In general you should use this library if you want to do fancy things with numbers, especially if you have matrices or arrays. We can import NumPy using:

import numpy

Importing a library is like getting a piece of lab equipment out of a storage locker and setting it up on the bench. Libraries provide additional functionality to the basic Python package, much like a new piece of equipment adds functionality to a lab space. Just like in the lab, importing too many libraries can sometimes complicate and slow down your programs - so we only import what we need for each program. Once we’ve imported the library, we can ask the library to read our data file for us:

numpy.loadtxt(fname='inflammation-01.csv', delimiter=',')

array([[ 0., 0., 1., ..., 3., 0., 0.],

[ 0., 1., 2., ..., 1., 0., 1.],

[ 0., 1., 1., ..., 2., 1., 1.],

...,

[ 0., 1., 1., ..., 1., 1., 1.],

[ 0., 0., 0., ..., 0., 2., 0.],

[ 0., 0., 1., ..., 1., 1., 0.]])

The expression numpy.loadtxt(...) is a function call

that asks Python to run the function loadtxt which

belongs to the numpy library. This dotted notation

is used everywhere in Python: the thing that appears before the dot contains the thing that

appears after.

As an example, John Smith is the John that belongs to the Smith family.

We could use the dot notation to write his name smith.john,

just as loadtxt is a function that belongs to the numpy library.

numpy.loadtxt has two parameters: the name of the file

we want to read and the delimiter that separates values on

a line. These both need to be character strings (or strings

for short), so we put them in quotes.

Since we haven’t told it to do anything else with the function’s output,

the notebook displays it.

In this case,

that output is the data we just loaded.

By default,

only a few rows and columns are shown

(with ... to omit elements when displaying big arrays).

To save space,

Python displays numbers as 1. instead of 1.0

when there’s nothing interesting after the decimal point.

Our call to numpy.loadtxt read our file

but didn’t save the data in memory.

To do that,

we need to assign the array to a variable. Just as we can assign a single value to a variable, we

can also assign an array of values to a variable using the same syntax. Let’s re-run

numpy.loadtxt and save the returned data:

data = numpy.loadtxt(fname='inflammation-01.csv', delimiter=',')

This statement doesn’t produce any output because we’ve assigned the output to the variable data.

If we want to check that the data have been loaded,

we can print the variable’s value:

print(data)

[[ 0. 0. 1. ..., 3. 0. 0.]

[ 0. 1. 2. ..., 1. 0. 1.]

[ 0. 1. 1. ..., 2. 1. 1.]

...,

[ 0. 1. 1. ..., 1. 1. 1.]

[ 0. 0. 0. ..., 0. 2. 0.]

[ 0. 0. 1. ..., 1. 1. 0.]]

Now that the data are in memory,

we can manipulate them.

First,

let’s ask what type of thing data refers to:

print(type(data))

<class 'numpy.ndarray'>

The output tells us that data currently refers to

an N-dimensional array, the functionality for which is provided by the NumPy library.

These data correspond to arthritis patients’ inflammation.

The rows are the individual patients, and the columns

are their daily inflammation measurements.

Data Type

A Numpy array contains one or more elements of the same type. The

typefunction will only tell you that a variable is a NumPy array but won’t tell you the type of thing inside the array. We can find out the type of the data contained in the NumPy array.print(data.dtype)dtype('float64')This tells us that the NumPy array’s elements are floating-point numbers.

With the following command, we can see the array’s shape:

print(data.shape)

(60, 40)

The output tells us that the data array variable contains 60 rows and 40 columns. When we

created the variable data to store our arthritis data, we didn’t just create the array; we also

created information about the array, called members or

attributes. This extra information describes data in the same way an adjective describes a noun.

data.shape is an attribute of data which describes the dimensions of data. We use the same

dotted notation for the attributes of variables that we use for the functions in libraries because

they have the same part-and-whole relationship.

If we want to get a single number from the array, we must provide an index in square brackets after the variable name, just as we do in math when referring to an element of a matrix. Our inflammation data has two dimensions, so we will need to use two indices to refer to one specific value:

print('first value in data:', data[0, 0])

first value in data: 0.0

print('middle value in data:', data[30, 20])

middle value in data: 13.0

The expression data[30, 20] accesses the element at row 30, column 20. While this expression may

not surprise you,

data[0, 0] might.

Programming languages like Fortran, MATLAB and R start counting at 1

because that’s what human beings have done for thousands of years.

Languages in the C family (including C++, Java, Perl, and Python) count from 0

because it represents an offset from the first value in the array (the second

value is offset by one index from the first value). This is closer to the way

that computers represent arrays (if you are interested in the historical

reasons behind counting indices from zero, you can read

Mike Hoye’s blog post).

As a result,

if we have an M×N array in Python,

its indices go from 0 to M-1 on the first axis

and 0 to N-1 on the second.

It takes a bit of getting used to,

but one way to remember the rule is that

the index is how many steps we have to take from the start to get the item we want.

In the Corner

What may also surprise you is that when Python displays an array, it shows the element with index

[0, 0]in the upper left corner rather than the lower left. This is consistent with the way mathematicians draw matrices but different from the Cartesian coordinates. The indices are (row, column) instead of (column, row) for the same reason, which can be confusing when plotting data.

Slicing data

An index like [30, 20] selects a single element of an array,

but we can select whole sections as well.

For example,

we can select the first ten days (columns) of values

for the first four patients (rows) like this:

print(data[0:4, 0:10])

[[ 0. 0. 1. 3. 1. 2. 4. 7. 8. 3.]

[ 0. 1. 2. 1. 2. 1. 3. 2. 2. 6.]

[ 0. 1. 1. 3. 3. 2. 6. 2. 5. 9.]

[ 0. 0. 2. 0. 4. 2. 2. 1. 6. 7.]]

The slice 0:4 means, “Start at index 0 and go up to, but not

including, index 4.”Again, the up-to-but-not-including takes a bit of getting used to, but the

rule is that the difference between the upper and lower bounds is the number of values in the slice.

We don’t have to start slices at 0:

print(data[5:10, 0:10])

[[ 0. 0. 1. 2. 2. 4. 2. 1. 6. 4.]

[ 0. 0. 2. 2. 4. 2. 2. 5. 5. 8.]

[ 0. 0. 1. 2. 3. 1. 2. 3. 5. 3.]

[ 0. 0. 0. 3. 1. 5. 6. 5. 5. 8.]

[ 0. 1. 1. 2. 1. 3. 5. 3. 5. 8.]]

We also don’t have to include the upper and lower bound on the slice. If we don’t include the lower bound, Python uses 0 by default; if we don’t include the upper, the slice runs to the end of the axis, and if we don’t include either (i.e., if we just use ‘:’ on its own), the slice includes everything:

small = data[:3, 36:]

print('small is:')

print(small)

The above example selects rows 0 through 2 and columns 36 through to the end of the array.

small is:

[[ 2. 3. 0. 0.]

[ 1. 1. 0. 1.]

[ 2. 2. 1. 1.]]

Arrays also know how to perform common mathematical operations on their values. The simplest operations with data are arithmetic: addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. When you do such operations on arrays, the operation is done element-by-element. Thus:

doubledata = data * 2.0

will create a new array doubledata

each element of which is twice the value of the corresponding element in data:

print('original:')

print(data[:3, 36:])

print('doubledata:')

print(doubledata[:3, 36:])

original:

[[ 2. 3. 0. 0.]

[ 1. 1. 0. 1.]

[ 2. 2. 1. 1.]]

doubledata:

[[ 4. 6. 0. 0.]

[ 2. 2. 0. 2.]

[ 4. 4. 2. 2.]]

If, instead of taking an array and doing arithmetic with a single value (as above), you did the arithmetic operation with another array of the same shape, the operation will be done on corresponding elements of the two arrays. Thus:

tripledata = doubledata + data

will give you an array where tripledata[0,0] will equal doubledata[0,0] plus data[0,0],

and so on for all other elements of the arrays.

print('tripledata:')

print(tripledata[:3, 36:])

tripledata:

[[ 6. 9. 0. 0.]

[ 3. 3. 0. 3.]

[ 6. 6. 3. 3.]]

Often, we want to do more than add, subtract, multiply, and divide array elements. NumPy knows how

to do more complex operations, too. If we want to find the average inflammation for all patients on

all days, for example, we can ask NumPy to compute data’s mean value:

print(numpy.mean(data))

6.14875

mean is a function that takes

an array as an argument.

This episode demonstrates all the features that can be used when writing a lesson in RMarkdown.

To generate the site, you will need to have the following packages installed:

install.packages(c("knitr", "stringr", "checkpoint"))

If the lesson uses additional packages, the script that converts the Rmd files

into markdown, will detect them and install them for you, when you run make

serve or make site.

This first chunk is really important, and need to be included at the beginning of each episode written in RMarkdown.

source("../bin/chunk-options.R")

The rest of the lesson should be written as a normal RMarkdown file. You can include chunk for codes, just like you’d normally do.

Normal output:

1 + 1

[1] 2

Output with error message:

x[10]

[1] NA

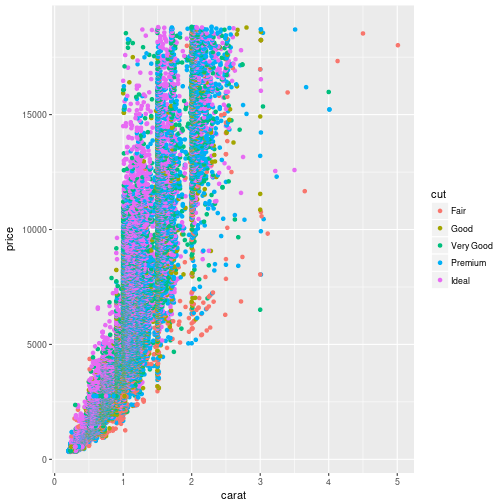

Output generating figures:

library(ggplot2)

ggplot(diamonds, aes(x = carat, y = price, color = cut)) +

geom_point()

For the challenges and their solutions, you need to pay attention to where the

> go and where to leave blank lines. You can include code chunks in both the

instructions and solutions. For instance this:

> ## Challenge: Can you do it?

>

> What is the output of this command?

>

>

> ~~~

> paste("This", "new", "template", "looks", "good")

> ~~~

> {: .language-r}

>

> > ## Solution

> >

> >

> > ~~~

> > [1] "This new template looks good"

> > ~~~

> > {: .output}

> {: .solution}

{: .challenge}

will generate this:

Challenge: Can you do it?

What is the output of this command?

paste("This", "new", "template", "looks", "good")Solution

[1] "This new template looks good"

Key Points